Things can get lost in translation. Or sometimes added…

This afternoon I found myself looking for a specific historical reference to use in one of my incredibly erudite Facebook posts. (I forget what the topic was: I suppose it says something about me that I remember making the extra effort to sound really smart, but I don’t for the life of me remember what we were talking about, or why it was necessary to impress anybody.)

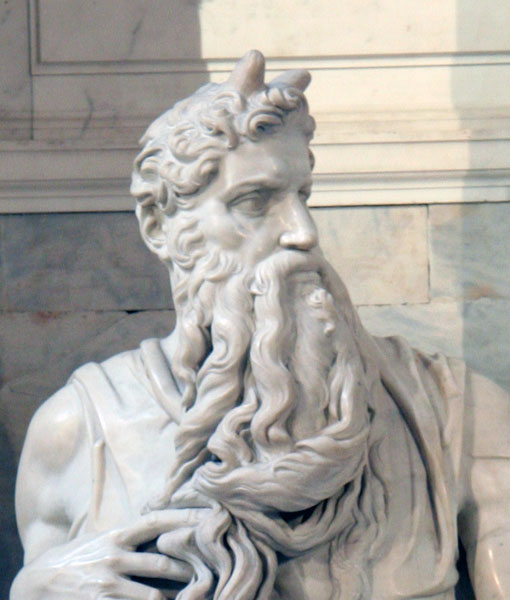

Michelangelo’s statue of Moses in Rome shows a bearded man with two horns sticking out of his forehead. This was because by Michelangelo’s day the Old Testament had been translated and re-translated, and some inevitable confusion had crept in. The original Hebrew text had described rays of light coming out of Moses’ face, but in the process of translation the words used to describe Moses’ halo were misread as referring to horns. Eventually, scholars learned to rely less on the work of other scholars and to check these things for themselves, but by then the damage had been done.

Anyway, I was looking for the origin of a particular anecdote, and I did what every enterprising modern scholar does: I Googled it. There were quite a few results, and I opened up the first half dozen or so, pleased at having solved my problem so quickly and efficiently.

I soon noticed, however, that each of the entries I found seemed to consist of the same text; paraphrased in some cases, but clearly recognizable. Pages upon pages of Google search results showed me much the same thing. There were, as far as I could tell, only two or three original paragraphs that had been passed around like a bucket of popcorn. A few people had left greasy fingerprints, rearranging a sentence or two, adding or subtracting some parenthetical notes, but generally it was clear that we had all been eating out of the same bucket. Worse yet, no one felt the need to identify the original source; I suspected that many of the entries I was reading had actually been plagiarized from each other, generations removed from the original material.

I already know what I want it to say. I don’t have to read it.

In almost any serious intellectual discipline there is a principal of “primary sources”, intended to avoid just this problem. This means that if you are looking for information about the First Amendment to the US Constitution, you begin by reading the actual First Amendment to the US Constitution, not a Wikipedia article about freedom of speech.

Unfortunately, this can be time-consuming, and not everyone has access to original documents, or the expertise to know what they were seeing if they did. We rely a lot on “experts”, whose qualifications may themselves be based on little more than the interpretation or popularization of the work of others.

Cable news commentators don’t interview scientists, they interview each other about what the scientists might have said. Very few laymen are likely to go back and read some scholarly paper in the Journal of the Society of American Endocrinologists, just to check up on the talking heads. It’s not hard to invoke George Washington or Saint Paul to support my point of view if I don’t have to actually refer to any actual text. I assume that George Washington believes what I say he believes, I don’t have to look it up in some book.

In the end, any information about an event in which we ourselves did not take part is going to be second-hand, at the very least. We’re constantly immersed in a soup of information, especially now during the political silly season, and we don’t always have the time or resources to check every fact — let’s just remember, please, that every soup can benefit from a grain of salt.

* * *

Leave a Reply