“Aseneth” — Mixed media, 8 x 10 inches.

I’ve recently undertaken a couple of pieces of artwork that involved human faces. In both cases, the style of the piece was such that I had a lot of leeway — I wasn’t looking for some sort of photorealistic presentation, I just needed a female face. The only requirement was that the face be beautiful, and that the look not obviously belong to a particular time or place.

For one of the projects I was working on — “Andromeda”, the Greek myth of the daughter of Cassiopeia and Cepheus — I ended up using a variation of the style of illustration used on ancient Greek pottery. The style, itself timeless, suited the story, and the simplification and stylization avoids the kind of detail that dates an image. This was, however, a bit of a cop-out, since I wasn’t really solving the problem, just restating it in a way that made the question irrelevant.

For the other project — “Aseneth”, based on the apocryphal story of the wife of Joseph (son of Jacob) — I didn’t have a ready-made solution available. The Hebrews of Old Testament times produced little in the way of lasting visual art; unlike their more sedentary neighbors in Africa and Mesopotamia their constant warfare and nomadic lifestyle did not encourage lasting artistic monuments, and the dictates of religion (“create no graven image”) made permanent representations of people problematic. There are no paintings or figurines like those of the Minoans, no epic tales painted on stone or papyrus like those of the Egyptians.

Here, also, we face the differing standards of culture and race: late Egyptian sarcophagus portraits show women with carefully cultivated Frida-Kahlo-esque uni-brows. Phoenician women were depicted with large noses and tiny waists; Persian women were depicted with vanishingly small noses but hips and thighs that we would view today as almost obese. What would a beautiful woman of the book of Genesis look like?

In practice, this turns out to be a lot harder than it sounds. Anyone who’s watched a movie or television show that was billed as “stylish” at the time of its release knows how bizarre yesterday’s standards of beauty can look, even within a single lifetime: Joan Crawford’s shoulder pads in 1940, Joan Cusack’s teased hair in 1988; Marilyn Monroe’s curves, Mary Tyler Moore’s boyish lines; Brooke Shields’ heavy straight eyebrows, Louise Brooks’ penciled-in arches … We look at the women we once considered beautiful and today we find them jarring, unreal; the paragons of their time, alien to ours.

So, what to do when you want to specify that your subject is “beautiful”, but you don’t want her to be so much a product of one era — either ours or her own?

Throughout history artists have generally depicted the men and women of times and places remote from their own according to the styles most familiar and comfortable to them. This was often for very valid economic reasons: make your Cleopatra look like the wife of a wealthy patron and you’ve got a much better chance of finding a buyer for the painting. The influence of the Church or government could also impact fashions, and could dictate the need to reflect their concerns even in depictions of persons and scenes completely foreign to either. During the eighteenth century, the gods and goddesses of classical mythology were presented in the fluffy, frilly world that the French monarchs enjoyed, frolicking in voluptuous but tasteful nudity; by the twentieth, those same figures were more often portrayed shrouded in drapery, lurking in a dark and dramatic pagan wilderness.

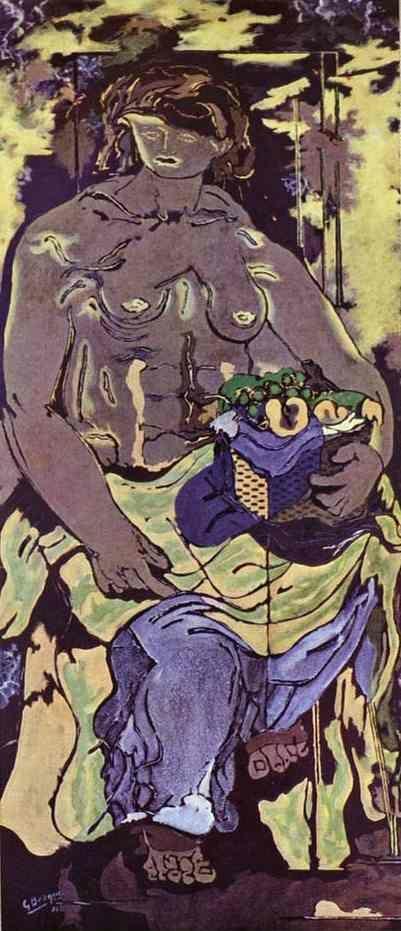

George Braque, Canéphore, 1926

More recently, artists have sidestepped the question: Paul Klee depicts a female saint as a delicate scribble of lines; Mark Rothko’s Iphigenia is a striated black cone with a pair of stick legs and no head; Georges Braque’s canephorae are massive, lush figures, small-breasted and heavy-bodied, fleshy and androgynous.

Klee observed in his Bauhaus lectures that simplification was the key to making an image universal. A child’s stick figures are recognizable as human and timeless; only when we start to elaborate on the basics do we begin to limit the image to a particular time and place. Rothko dissected his figures, reducing them to symbolic fragments that could only be read as human by someone who had learned to “read” his visual shorthand.

But how do you define a stick figure or a symbol as “beautiful” or “terrifying” or “modest”? What makes a stick figure of Andromeda waiting to be devoured by the monster different from a stick figure of the god Poseidon ordering the monster to eat her? The answer to this question is actually fairly easy: context. Poseidon is not chained up on the rocks at the water’s edge; Andromeda is not rearing from the waves brandishing a trident.

But beauty? Can this be defined by context? I think so. When Picasso paints a wildly distorted image of his lover staring at her own reflection in a mirror, we understand that she likes what she sees, and so does he. Braque’s canephorae are massive and fleshy, but they are also luminous, ripe, like the fruit spilling from the baskets they carry; their lavish health and vigor makes us know that they are beautiful, much more than their tiny, simplified faces ever could — even further, their beauty is timeless, independent of fashion or custom.

What Klee doesn’t mention when he makes his observations about simplification is the importance of the artist’s personal commitment: like the fashionable painter with his Cleopatra, it is much harder to meet the demands of an objective art than to fall back onto a marketable adherence to current standards. In other words, it is easier to paint an Aphrodite who looks like Kiera Knightley than one represented by a mysterious map of arcane symbolism. Picasso’s images of women are not for everyone: they have to be interviewed, read, their context and their attitude deciphered; Braque’s nudes would not be welcome on a fashionable beach; and Klee’s whimsical scribbles could never even exist outside the pictures that they inhabit.

But there is something to be said for immortality, after all: when an image operates outside of current fashion its message is not so likely to be obscured by superficial considerations of taste and style. Symbols endure while trends in hair and makeup change with the seasons. Katherine Hepburn once observed that age was liberating — once she got past fifty, moviegoers lost interest in her hair and her clothes and they started paying more attention to her acting.

The projects I’m working on today are a bit more esoteric than “Andromeda” or “Aseneth”. Neither has human figures in it (at least not recognizably), so I have some time to think about all this before the question comes up again. The visual depiction of beauty that has nothing to do with appearance: this is going to be interesting.

* * *

Leave a Reply