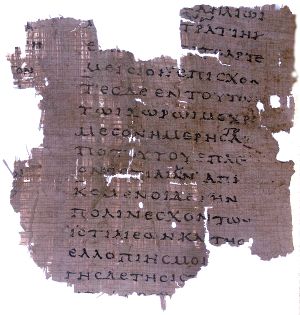

My copy is somewhat more up to date than this one.

I was poking around among the bookshelves a day or so ago, looking for something to entertain me as the first cool weather of the season settles in, when I spotted my rather tattered Penguin Classics copy of the Histories of Herodotus.

This is one of those books that I like to read once every decade or so. It’s long (over 620 pages in this edition), and the print gets smaller every time I pick it up, but there’s something cozy and comforting about it, like that sweater that you would never dream of wearing where people could see you, but that’s perfect for puttering around the house. There’s enough snob value in just having the book in your hand that you don’t have to slave over the really heavy parts; when the political stuff gets dull you can always skip to the stories about headless cannibals roaming the Libyan desert or the bedroom antics of the King of Lydia, his wife, and the palace guard.

Herotodus lived and worked during the decades on either side of about 450 BC, born in what is now Bodrum, Turkey, then a Greek town called Halicarnassus. We know that he traveled a lot and talked to a lot of people – although how much he traveled and how many people he actually talked to is a subject for some debate.

The Roman orator Cicero, some three and a half centuries later, called Herotodus the “Father of History”.

More recent commentators have called Herodotus the “Father of Lies”.

*

Every now and then somebody reading one of my blog posts takes exception to a bit of data – a statistic, a description, or some discreet character assassination – that I may have included without having identified my source.

If what I was doing was serious research, or scholarly investigation, or even journalism, this would be a valid and important concern, but these essays are just my personal ruminations on subjects that interest me: I strive for accuracy, and I am prepared to defend any factual data that I use, but I don’t think footnotes are really necessary.

And let’s face it: some of my posts are long enough as it is.

A few of the folks who worked with me during my years in television newsrooms will no doubt remember my obsession with factual accuracy. I’m a product of an era when the comments of “unnamed sources” did not make it into front page news, and phrases like “some experts have suggested” or “individuals close to the case have indicated” were systematically – and sometimes brutally – rooted out of the aspiring journalist’s repertoire by the time he or she graduated high school.

When I’m assembling information for a blog post, I usually begin with a topic with which I am already pretty conversant, and then fill in the blanks from there. I look for primary sources where I can find them – if I am going to quote from the book of Genesis, for example, I go get the Bible down and look up the chapter and verse: I don’t pull something from the collected wit and wisdom of Jimmy Swaggert and hope for the best – and if primary sources are not available, I make sure that whoever I’m relying upon has the right credentials.

I’m not trying to expand the scope of human knowledge: I’m looking for context and connections. I’m just an interested amateur talking about things that I think are worth talking about.

History, like political commentary, is one of those fields that attracts a lot of amateurs.

The chemist or the molecular biologist is not likely to feel any sort of innate personal affinity with a hydrogen nucleus or a molecule of adenosine triphosphate. The subject matter demands rigor and discipline; nobody just assumes that he’ll be able to pick it up by reading a couple of articles in Discover magazine. The history buff, on the other hand, is dealing with people just like himself, flesh-and-blood men and women who got up in the morning and ate breakfast and argued with their children and fed their pets and worried about the rent just like everybody else. It’s easy to feel that you know more than you really do. There’s something very subjective about history: once you get past the names and dates, there always seems to be a lot of room for interpretation.

*

Over the centuries Herodotus has drifted in and out of fashion. As more scientific methods of approaching historical research led to new insights in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, scholars began to downgrade the old personal-narrative style of historical writing; Herodotus, Procopius, Tacitus and others were increasingly viewed as, at best, commentators, and at worst, fabulists and liars, using history as a vehicle for political, social, religious or cultural illustration without any real commitment to objective facts. This did not necessarily diminish their popularity as authors, but their contributions to modern understanding of the times in which they had lived were viewed as less meaningful from a historical perspective.

History, like the sciences, had become focused on attempting to document an objective reality.

In practice, of course, there is no such thing, at least not in terms of our ability to observe and communicate what we are able to learn. Everyone filters reality through a prism of personal experience, cultural expectations, and social limitations. [see also House of Mirrors, a previous essay in this blog] In today’s information-saturated world, separating fact from fable has become so difficult that we often don’t even bother any more. We’re like ants standing in the path of an avalanche of sand.

Herodotus wrote of a race of ants the size of bobcats living in the deserts of what is now Afghanistan who dug through the sand for gold with which to line their tunnels.

News outlets routinely present a view of reality that owes more to the expectations of sponsors and stockholders than to any commitment to documenting real events. In Colorado and Texas educational authorities are working at this very moment to rewrite history books in order to remove anything that offends their present-day political outlook. Everyone has an axe to grind, or a skeleton to hide.

Father of History/Father of Lies: who do we trust?

What really matters in the end is not what the writer is doing, but whether the reader has the critical capacity that will allow him or her to categorize and qualify what is being said, separating useful data from the distracting overlay of the writer’s intentions. We’re not just hollow vessels waiting to be filled with information: each of us has the ability to apply logic and reason to the information, developing a context, a matrix against which we can judge each new fact as it appears.

Father of Lies/Father of History: does it really matter?

It’s not up to the historian – or the politician, or the preacher, or the pundit – to decide what is fact and what is fiction. All they can do is explain their particular point of view, to build up that mountain of sand grain by grain.

It’s up to us to find the particles of gold in it.

* * *

Leave a Reply