I was awakened this morning bright and early by a phone call, which is never a good thing.

The cheery female voice that greeted my less-than-gracious hello-noise was that of a computerized telemarketing system which proceeded to remind me that I did not yet have a plan in place for disposing of my sad remains should I drop dead at any moment, my “final major expense”, as she/it put it.

Although she was absolutely correct, this is not a topic that I necessarily want to deal with before my Fruit Loops, and not over the phone. I hung up on Graveyard Gertie and put the question of what kind of treatment I might expect from my survivors in the event of my demise aside for the moment, to deal with a more pressing concern: the pounding headache behind my eyes that had made its presence known the moment I stood up to answer the phone. Funeral plans would have to wait: I was suffering from cedar fever.

“Cedar fever” is the winter equivalent of hay fever, with the allergen being cedar pollen rather than grass. Or more correctly, the culprit is juniper pollen: there are two species of juniper that are known to allergy sufferers all over the south and the southern plains, Juniperus virginiana, the Eastern Red Cedar, and the closely related Mountain Cedar, Juniperus ashei. These trees bloom in winter, at a time when hay-fever sufferers might reasonably expect some relief, so cedar-season can be particularly heartbreaking for those of us who have only barely dried out from the last allergy outbreak in the fall. Mountain Cedar blooms first, in February, followed by Red Cedar in late February and into March. People who are allergic to one are usually allergic to the other, so victims can count on at least two or three months each year of headache, fever, rusty mucus and burning eyes.

The pollen of these two plants is unusual among allergens in that the active ingredient is a single glycoprotein, high in carbohydrate and low in protein: as any dieter can tell you, carbs hit your system hard and hit it quickly compared to proteins. (Most pollen allergens are a mix of different glycoproteins, with mostly lower carbohydrate content, so the effect is less immediate, and less severe; you may be susceptible to one or two of the ingredients, but they’re diluted by the rest. With juniper pollen, if you’re allergic, you’re allergic, no shades of gray, and the effects are immediate: by the time you start sneezing, it’s too late.) Worse, because these are plants specifically adapted to wide open spaces, the pollen is fine and readily windborne, traveling miles on the slightest breeze, so you don’t have to have the damned things growing outside your bedroom window to feel the effects.

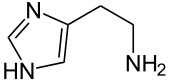

The worst symptoms of allergies, and for that matter, the basic head cold, are actually self-inflicted. Our bodies react to any potential attacker coming in through the nose or mouth or other mucus membranes with what is known as the “histamine response”.

2-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)ethanamine, AKA histamine

Histamine is a nitrogen compound that opens up the capillaries to allow white blood cells and certain proteins involved in the immune response to reach and destroy any possible pathogens. Unfortunately, this means the affected tissues become puffy and wet, and the dead and dying casualties of battle have to be sloughed off and … well, ejected — one way or another. Even after the pathogen has been eliminated, it can take a while for the affected tissue to be cleared away, so the forty-eight hours or so of an active rhinovirus infection gives us the week to ten days of a head cold.

What can you do? Nothing much, unless you’re one of those people who doesn’t mind sealing himself indoors for several months out of the year with filtered air and no outdoor activities. For the rest of us, who have to go to work, or the grocery store, or who just want to throw open a window now and then, especially as winter loosens its grip, it’s pretty much a case of grimace and bear it. For myself, I’m experimenting with a sort of desensitization therapy, adding a few crushed juniper berries to my tea a couple of times a day: there’s certainly no clinical evidence to suggest that this actually does anything, but it is a well-known folk remedy, and I refuse to spend three months in an antihistamine daze.

There are organizations that advocate obliterating the trees everywhere they occur, and there are days when I lean toward joining up, and even sending a check. On the other hand, for the remaining nine or ten months out of the year, cedar trees are not unattractive, and birds eat the fruit (actually fleshy cones that just look like berries, but that’s neither here nor there), so I’m willing to endure.

If I find that consuming small doses of juniper does help, then things could get considerably more interesting: juniper berries are the principal flavoring agent in gin. G&T with those Fruit Loops, anyone?

* * *

Did your experimental consumption of crushed juniper berries help?

As a matter of fact, I think they did. I got through a couple of seasons without a serious allergy outbreak, but then this year I stopped using the juniper berries (those suckers are expensive!) and I am at this very moment hacking and sneezing my brains out with a hayfever attack. It’s always hard to be certain of cause and effect in these situations: maybe there was something different about the weather, or the rainfall, influencing the production of airborne allergens? Maybe there was a placebo affect? I don’t know, but I’ve decided that even if there’s only a small chance that the berries made a difference, it’s worth it to me from now on to continue to use them.

Have to agree. This year is incredibly difficult for me. I am very ill from it this year. Our drought year was easier. Our pool has a layer of yellow powder on it this year, and I am having extreme symptoms. I think I may try drinking juniper tea all year this year every day, to see what happens next season. I am actually sick from it this year, and my face is swollen, and I have difficulty swallowing. Juniper is horrible.