The devil made me buy this dress …

The thing that I find most disturbing about Toronto mayor Rob Ford’s ongoing meltdown is not the crack smoking, or showing up stoned at a charity function for wounded soldiers, or calling a south-Asian taxi driver “Paki”, or threatening — on video — to grab an automatic weapon and slaughter his political opponents. What shocks me most are his constant expressions of outrage and wounded pride at being called to account for his actions.

So many elected officials — not just here in the US, mind you, but even in the sedate world of Canadian politics — seem to reach a certain point in their careers at which they feel that they are beyond the need for apologies, beyond accountability, beyond all personal responsibility. When the shit hits the fan, they blame the fan for the mess that ensues.

Perhaps this is simply an extension of the cult of celebrity that surrounds many elected leaders today: they are described as “media darlings”, “rising stars”, “shining lights” — the same sorts of expressions that might be applied to a pop singer or a professional athlete. Intelligence, hard work, and dedication may be there, but those don’t make very compelling news copy: we’re far more interested in how quickly the individual has risen to prominence, or in whose company, or on the back of what theatrical rhetoric. When faced with this sort of deification day after day, who wouldn’t begin to feel as though he (or more rarely she) is somehow beyond the ordinary rules of right and wrong?

- Kentucky Senator Rand Paul, called to account recently for a string of obvious and egregious plagiarisms in his public speeches and writings, has made it clear that the skunk in the woodpile is not the high-profile political figure who steals from others, but the press and pundits who keep catching him at it.

- Former US Representative Anthony Weiner, when caught sending sexually explicit text messages and photos to a series of young women around the country, offered a somewhat half-hearted apology then turned on the media for “persecuting” him — after which he continued to send sexually suggestive messages to women, still complaining all the while of his mistreatment by the press.

In centuries past, public officials viewed bribery and extortion as a perquisite of the job. Why else would anyone subject themselves to the aggravations of holding office? “Baksheesh”, a Persian word that became widespread in the days of the Ottoman Turkish empire, could mean a tip, a contribution, or a bribe, interchangeably; today we pretend that these things are actually separate and distinct, but in politics, little has changed. The line between a campaign contribution and a bribe is drawn with a very light pencil; “personal time with friends” can mean anything from a weekend of golf courtesy of the Koch brothers to a drug-addled rampage in a suburban crack den.

Marion Barry, David Vitter, Larry Craig, Kwame Kilpatrick: the list is depressingly long. In so many cases, the individuals involved had no prior history of corruption or sexual misadventures or substance abuse: only after achieving positions of power and prominence did the imp of the perverse take control. (Admittedly, until these men became important, the mainstream press was hardly likely to be interested in their pecadilloes, but given the microscopic scrutiny that politicians must undergo during the endless cycles of campaigning and politicking, it seems unlikely that ongoing problems of such severity would have escaped notice.) More importantly, once caught with their hands in the cookie jar (or down their boxer-briefs) they are invariably shocked — shocked — that people might hold them responsible for their own actions.

According to British historian Lord Acton (John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton, 1834–1902): “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.” This is a phenomenon that is not difficult to understand, even by those of us who have never had the opportunity to wield — or abuse — power. What Lord Acton doesn’t mention is the inability of powerful men to accept the blame for their own sins, which I personally find much harder to accept. We all make mistakes, but not all of us have thousands, even millions, of other people depending on our honesty and integrity, trusting us to do the right thing — and when in the wrong, to ‘fess up, to make amends, and to make a real and sincere effort to do better in the future.

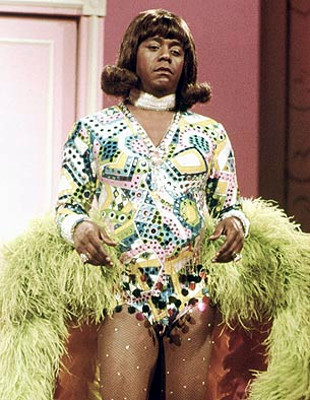

Whenever Geraldine Jones — frisky alter-ego of funnyman Flip Wilson in the early 1970s — would find herself caught in an indiscretion, she didn’t lash out at her accusers: she generally had the good grace to admit her mistakes, and her excuse — “the devil made me do it!” — was certainly as good as any I’ve heard lately.

* * *

In today’s installment of the Rob Ford saga, he has publicly apologized for a bout of obscenity that he unleashed on reporters when confronted by a report that he had attempted to force oral sex on a staff member; he then followed up the apology with a series of threats against former staffers who outed him on his past drug and alcohol abuse. Some guys just never quite get it.

Today we’re digesting the news that Congressman Trey Radel, Republican from Florida, is facing misdemeanor cocaine possession charges in Washington, DC. Had he been caught in his home state of Florida, where he has been a champion of tough drug sentencing laws, he would be charged with a felony — a guilty plea or conviction would result in the loss of his right to vote and to carry a firearm. In his previous job, he was a tough-talking Tea Party conservative TV and radio talk show pundit. “Do as I say, not as I do…” He’s blaming a problem with alcohol.