In 1966, just as the war in Vietnam was hitting its stride, my father retired from the US Air Force.

Packing up the wife and three small children (the oldest — me — having just completed the second grade) he returned to the town of his own childhood, a place in the Appalachian foothills of northern Alabama with the peculiar name of Boaz.

Moving was nothing new for us: by that time I had lived in military bases in Montgomery, Alabama (twice); Biloxi, Mississippi; Syracuse, New York; and had even spent a short spell in Boaz while my father was serving a stint in Vietnam. I knew that stability was fragile, possessions a burden, and that friendships had to be quick to form and shallow enough to walk away from without pain.

The final move to Boaz, however, was different. A military base is a special world for a small child, safe and vivid and full of excitement and mystery; Boaz was … well, quiet. No recruits double-timing down the street in front of the apartment; no decommissioned fighter jets parked in vacant lots, swarming with small children (for whom a chain-link fence was more an invitation than a barrier); no Commissary; no PX; no movie theater just around the corner; no library.

Despite having spent most of my life up to that point in the deepest Deep South, I did not have a southern accent — my mother, a transplanted New Englander, had bequeathed me her more precise grammar and neutral delivery. I was fairly well-read for my age (thanks to the easy access to books on base) and my previous schools had been somewhat more advanced that the one I now found myself attending. Teachers seemed irritated, even antagonized, by my efforts to please. Classmates were suspicious, sometimes hostile. The transition went from awkward to uncomfortable to excruciating in no time at all.

The adaptability that goes with being a military brat assumes certain preconditions — an urban environment, a population of other kids with equally shallow roots, and the levelling effect of never being exposed to the same group of people for more than a year or two at a time. Boaz had none of these things. This was an environment where cliques had long since been sealed, newcomers remained newcomers for years, and everyone spoke with the same accent. I felt, sounded, looked alien. The only thing that kept me from diving under the bed and never coming out again was the idea, despite being told otherwise, that we would move again before too long, return to the real world, the world of tanks and books and soldiers singing rude songs as they trotted down the street.

“… Look down through the five senses like stars

Lawrence Durrell, “The Pilot”

To where our lives lie small and equal like two grains

Before Chance — the hawk’s eye or the pilot’s

Round and shining on the open sky,

Reflecting back the innocent world in it.”

Within a matter of months, just as the terrors of the new reality were taking firm hold, a family with a daughter my age moved in next door.

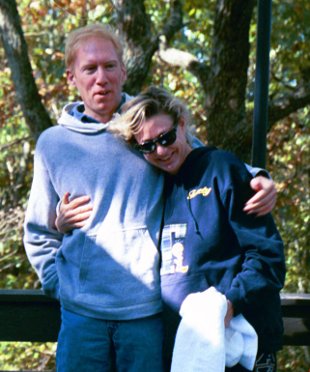

They were also from elsewhere, they were Air Force, they were also well-travelled, and Pam talked just like me. Naturally, we became friends — not in school, oddly enough, we were rarely in the same classes — but we spent much of our free time together, riding bikes, climbing trees, romping around in the cornfields (long since built over) behind our houses, tormenting our younger siblings, and talking, talking, talking.

After a year or so, Pam and her family moved around the corner, but remained within shouting distance. As time passed, we drifted in different directions — Pam was athletic, bright, heedless, the sort of person who excelled without obvious effort, while I was shy, small for my age, brainy, but an underachiever, irrationally terrified of my classmates and my teachers — but our bond endured.

By high school we had moved almost entirely into different worlds: apart from band (characteristically, I played clarinet while Pam played trumpet) we had little in common, and we each spent more and more time pursuing our separate interests.

College brought us together again, closer than ever, for a couple of years. We became almost inseparable. Teachers referred to us as brother and sister, and classified us as bright, but doomed.

Despite that renewal of our friendship, the separation that followed was more than just a relocation around the corner: Pam moved to Huntsville, fifty miles north, married, divorced; I moved to Birmingham, ninety miles south, stumbled through two more years of college, and then wandered off into a long and labyrinthine passage to adult life.

In the decades that followed we both moved, and moved again, changing as we went, putting ever more distance between us. By the time we reached our thirties, I had washed up in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Pam had come to ground in San Diego, California — we had finally managed to place an entire continent between us.

We still met, at widely spaced intervals, almost always in Boaz, on neutral ground. Pam had remarried, with stepchildren to look after, and I was building a career, so the visits were often brief.

At our twenty-fifth-anniversary high-school reunion, we made up for lost time, spending the last few days of the holiday in New Orleans, reliving the past, lying to each other about the future. Pam drank a bit, and smoked a lot — these were habits she developed early on, and polished as time went by. (I smoked for some years, but finally gave it up as simply requiring too much effort, and never had much capacity for alcohol.) By our mid-forties the differences in our lifestyles had become deep, but even on Bourbon Street at four a.m. I still kept seeing the girl next door behind the haze of jello-shots and nicotine.

A few years ago Pam and I saw each other — for the last time, as it happened — while she waited for a connecting flight at DFW Airport in Dallas. I drove out to the airport to meet her and we sat on a bench in the Texas sun for a couple of hours and chatted, just as we always had. Despite the heat, she was cold, bundled up in a jacket and furry boots; thinner than I had seen her, smoking one cigarette after another, her conversation wandering, clicking, sometimes stumbling, sometimes dancing. She was ill, but I did not understand that — perhaps I refused to understand that: I believed that she wasn’t taking care of herself, that she was over-tired, under-eating, typical Pam. For me, nothing else was possible. I avoided looking too closely, asking questions.

In the years that followed I failed to keep up, to maintain contact, more concerned with sustaining my illusions than with the person who wore them.

This week Pam moved again, moved even further away, and the continent that lies between us is one that can only be crossed once, and then only in one direction. She’s gone further from me than I ever thought possible, and I am less now than I was.

We spent more time apart than we did together over the last forty-eight years, but that means that there was little time for bad memories — our moments together were precious and important.

Even there on that airport bench, sitting in the sun watching the taxicabs creep past us, the shouting men, loaded with luggage, shrill women in uncomfortable shoes — even there, I remember clearly that, different as she was –as different as I was — one thing had not changed: I could hear forty years of echoes every time she laughed, and with every smile we were children again, strangers in a strange land, sharing.

* * *

Beautiful and touching story. Thanks for sharing…..

I just now got around to reading this and WOW … so beautifully put. I wish Pam could have read this. You have a way with words, just as you have a way with paint, etc.

We think we have time to tell the people who matter to us that they are special and that we will always love them. How wrong we are.