How about a round of badminton while we wait for the burgers to come off the grill?

Yes, it’s that time again. Winter is finally over, Ice Season is melting into slushy, gritty memories, and we’re moving into that other half of the year: Tick season.

Here in the Ozarks, tick season runs from about the first week in April through the end of December, with occasional outbreaks in January, February, and March. By mid-May roving hordes of the little monsters will be moving through the underbrush like piranhas with legs, armored specks of concentrated evil seeking whom they may devour.

We’re all becoming pretty current on the latest tick-borne diseases in humans, and the toll on pets is equally terrifying. Repellants, foggers and sprays fill the air like morning mist; gatherings of the beautiful people are aromatic with eau de permethrin, and the rest of us bathe in Deet as if were Chanel No. 5.

The awful truth, however, is that nothing seems to work: we cover ourselves with “Deep Woods Off” to cross the lawn to the mailbox, and by the time we get back to the front door with the junk mail our shoelaces are seething with activity.

At the risk of betraying an obsession, I will say that I have written on the subject of ticks before, focusing a little more on what they are rather than what they do: https://www.turningupbones.com/ticking-like-a-time-bomb/

What to do? Well, there are, in fact, two chemicals that are widely used to deal with ticks around the home: N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET for short), and permethrin.

Like the atom bomb and Agent Orange, DEET was invented by the US military in the latter stages of World War II; jungle warfare had taken a toll on soldiers who were not acclimated to the wide range of insect-borne diseases that they encountered in the Pacific and Asia, and the army wanted a single product that would defend against an assortment of pests. DEET is effective against the worst offender, the mosquito, not just repelling the creatures but killing them on contact. Unfortunately, it is only effective while still wet: once the application has dried completely, the hapless jungle warrior might just as well be slathered up with carrot puree. Furthermore, DEET is a powerful solvent, and will destroy rayon, nail polish, and spandex (“Holy holes in the tights, Batman!”) and is known to have toxic side effects on a very small percentage of humans. Mosquitos also lose their susceptibility to it after the first exposure, so it becomes less effective the longer you use it.

And ticks? Well, they don’t exactly slurp down DEET like it was coconut pie, but it might as well be: unless the tick actually ingests the chemical it has no effect, and the DEET is not recommended for application directly to a person’s skin, which is the only place where the tick would ingest it — in the act of biting, which would seem to defeat the purpose.

Permethrin is somewhat more effective against ticks: it kills on contact, and it continues to work even after it has dried; it will even remain active after repeated washings. In small doses it is not known to be toxic to humans — although, as with any insecticide, infants and breastfeeding mothers should avoid it, just to be safe. Toilet paper tubes stuffed with cotton that has been soaked in permethrin can be placed in locations frequented by mice, who use the cotton for nesting material, killing ticks at one of the early stages in their development without harm to themselves.

The downside? Permethrin is very harmful to cats even in small doses: flea and tick medications containing permethrin that are perfectly safe for dogs will kill cats outright. Permethrin also does not discriminate between “good” and “bad” arthropods: it will kill the mosquitos and ticks, but also the honeybees and spiders. If it gets into water it poisons fish, frogs and other aquatic life, and in large doses it can harm humans and other mammals. It persists in the environment for up to ten weeks, so repeated applications can result in dangerously high concentrations in and around the home.

This flyer from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (in PDF format) provides some pretty detailed information, including preventive measures, comparisons of insecticides and repellents, and treatment for tick bites. (The data used to compile this guide comes originally from the EPA, so if you’re a Republican you won’t want to read it.)

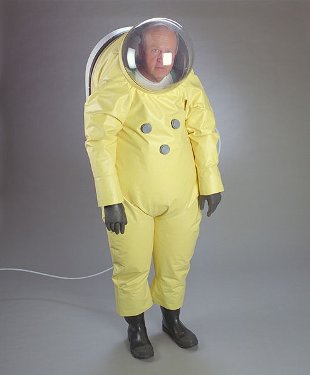

So chemistry still hasn’t provided a magic bullet. The old-fashioned approach is still the best: light-colored clothes covering the entire body so that ticks can be easily seen and brushed off, tightly-woven socks, pants tucked into boots — all those things that we so look forward to when the weather reaches 98 degrees with 85% humidity. Contrary to popular belief, ticks don’t drop out of the trees onto their prey — they can only see a few inches, so you’ve got to be on top of them before they’ll make their move — they simply crawl to the extreme end of leaves and twigs and wait for something to brush against their perch to they can grab on for dinner and a free ride. This means that the worst infestations can be avoided simply by keeping to the open trails, avoiding tall weeds and grass, and staying well away from underbrush. Tough rules to follow when you’re trying to mow the lawn or weed the garden, but every little bit helps. Ticks usually develop in stages on small, medium, and large hosts, so providing permethrin-treated bedding material for mice and packrats (you’ve got them, don’t fool yourself), fencing out deer, and keeping dogs and cats indoors will help break up the life cycle. Chickens and guinea hens eat ticks, so keeping a few fowl around the back door doesn’t hurt; opossums, although unlovely, are also known to nibble on the little devils.

So pull on your gumboots, tuck in your white jeans, duct-tape your gloves to your shirt cuffs, snuggle that collar up tight — and get out there and enjoy the great outdoors!

* * *

Two words: panty hose. Or is that one word?